Let’s skip back a moment, to 1985:

Writer/directors Ron Clements and John Musker: Pirates! In! Space!

Chairman of Walt Disney Pictures Jeffrey Katzenberg: No.

Ron Clements and John Musker: But! Pirates! In! Space!

Jeffrey Katzenberg: What about this “Great Mouse” thing you’ve been talking about? That sounded cute. And topical!

Or, to another moment, in 1987:

Ron Clements and John Musker: Pirates! In! Space!

Jeffrey Katzenberg: Or mermaids! In water!

Or to another moment, in 1990:

Ron Clements and John Musker: Pirates! In! Space!

Jeffrey Katzenberg: Still no.

Or to this moment, in 1993:

Ron Clements and John Musker: Pirates! In! Space!

Jeffrey Katzenberg: Really, guys—

Ron Clements and John Musker: Did you not see the live action Treasure Island this studio did decades ago? Or more specifically, how well it did at the box office?

Jeffrey Katzenberg: I did. You know what else did well at the box office?

Ron Clements and John Musker: Our last three films?

Jeffrey Katzenberg: Ok, true, but still. No.

Ron Clements and John Musker: Pleeeeeaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaassse!

Jeffrey Katzenberg: Get me another hit film, and then, maaaaaybe.

And then, 1998:

Ron Clements and John Musker, taking a deep breath: Pirates! In! Space!

Disney executives: Is there any way we can persuade you to drop this?

Ron Clements and John Musker: No. We love pirates. And treasure. And space!

Disney executives: Sigh.

It wasn’t that Clements and Musker disliked the films Disney assigned to them—The Great Mouse Detective, The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, and Hercules. But they really wanted to do their dream project: an adaptation of Treasure Island, set in space, but with space ships that looked like pirate ships. They had concept art, character sketches, a plot, and a dream. It had been one thing when the still unknown filmmakers had been assigned to The Great Mouse Detective instead of their dream film, and even The Little Mermaid. But as the box office results for the very successful Aladdin rolled in, Clements and Musker got impatient. They’d done what Disney wanted for three films. Now they wanted to do their dream film. Katzenberg was still unconvinced, but finally made a deal with them: if they did one more lighthearted, amusing film, they could have their pirates in space.

Reluctantly, the two set to work on Hercules.

By the time they were done, Katzenberg had left Disney to form Dreamworks Pictures. His successors at Disney were equally unenthusiastic about pirates and space. By this time, however, Clements and Musker were adamant. They had made four films for Disney that had all been box office hits. They deserved to make their dream film. Disney executives finally yielded, and the writer/directors plunged into a project that essentially proved a harsh truth: every once in awhile, you really shouldn’t follow your dreams.

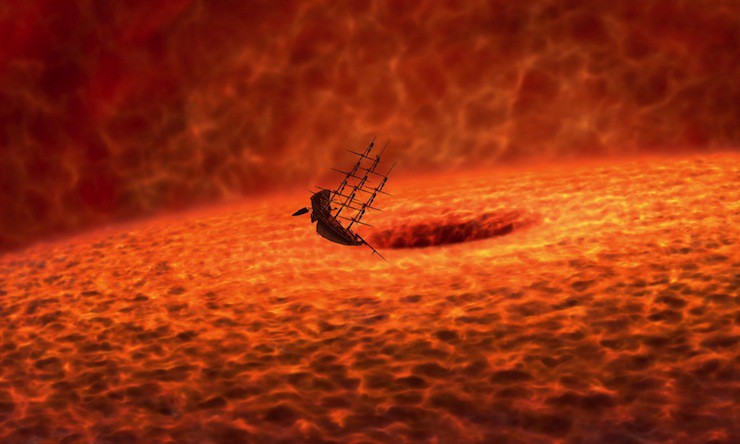

Because I’m about to get very harsh on this film, which is a cult favorite, a few quick points here: Treasure Planet is not a complete failure, unlike some of the other films discussed in this Read-Watch. It is unquestionably beautiful to look at, with daring and imaginative images—my favorite, perhaps, is the space ship port contained in a small crescent moon, but Treasure Planet has any number of wondrous images that I could have chosen from, including the treasure map at the center of plot, which opens to reveal a glorious map of stars. The multi-layered, central relationship between Jim, the main protagonist, and Long John Silver, the space pirate who both befriends and betrays him, is one of the richest and most convincing relationships Disney ever animated; if the entire film was nothing but the two of them, I would have no complaints at all. Unfortunately, it isn’t, but more of that in a bit.

Also, I love little Morph, Long John Silver’s little alien pet that can shift into various shapes at will. (Thus, Morph.) He’s cute, and I want one.

And now, the rest.

Treasure Planet opens on a note of combined rebellion and freedom, possibly a reflection of what Clements and Musker felt at this point, as Jim decides to do some solar surfing. This mostly serves as an opportunity for the filmmakers to assure viewers that the animation here would be as spectacular as it was in previous films: a combination of hand drawn animation and Disney’s Deep Canvas software, which had been used to such outstanding effect in Tarzan. Clements and Musker wanted Treasure Planet to have same sort of camera work as a James Cameron or Steven Spielberg film, which meant moving the camera a lot, which in turn forced animators to depend not just on the Deep Canvas software, but on small statues of every character that could be quickly rotated as references.

(As a bonus, the small statues were later put on display at Disney MGM-Studios as part of the Animation attraction; Disney would begin to do the same with many later productions. They are impossible to find now, but Disney cast members are hopeful that they will make an appearance someplace in the Hollywood Studios park once the current Star Wars and Pixar expansion is complete.)

The focus on moving the camera led to another innovation: designing 360 degree backgrounds, in contrast to the generally flat, partial backgrounds seen in previous Disney films. A few scenes—Belle’s dance with the Beast, the swooping camera work in the opening scene of The Lion King, and the Firebird sequence in Fantasia 2000—had come close to allowing a circling camera, but never completely achieved a full 360 background; Treasure Island perfected this, allowing the rooms of the pirate ship and space station to be seen from every angle. These backgrounds were innovative for another reason: for the first time ever in a Disney film: they are entirely digital, if based on 19th century oil paintings and the hand drawn illustrations from some of the earliest printings of Treasure Island. With added stars and nebulas, because, outer space.

Animators also relied on computers to help animate Long John Silver’s various appendages. They also used computers to help animate B.E.N., a robot whose artificial intelligence has gone a bit offline, Treasure Planet’s by now almost mandatory Professional Comedian Sidekick (in this case, voiced by Martin Short.) He’s not quite as entertaining as the original Ben in Treasure Island, but he does tell more jokes, so that’s something.

Otherwise, however, the filmmakers relied on good old fashioned hand drawn animation. Given the sheer number of characters with different body shapes and complicated costumes, this meant hiring an unusually high number of animators, which added to the expense of animating an already expensive film. In the end, this would be Disney’s most expensive animated film to date.

Which is why it’s kinda sad that so much of it makes no sense.

I mentioned, for instance, the image of the city nestled in the crescent moon. Beautiful, imaginative, a spectacular shot, one I’d be all about except for a lot of questions:

- Where is this moon?

- How is it holding its crescent shape? Moons generally come in two shapes: round, if they are large and heavy enough, and not round, if they are not. If they are not, they are generally not shaped like perfect crescent new moons, lovely though that image is. This moon is apparently only the size of a single city—let’s say Manhattan—so not that large, which brings up the next question: how does it have enough gravity to keep everything on its surface, especially since multiple people are walking around not at all bolted down, and the artificial gravity on the spaceship docked at this city doesn’t need to get turned on until the ship leaves the city, and also, how is anyone breathing?

The reason I end up asking these questions is that later, this film wants me to take the science seriously, throwing in an unexpected encounter with a supernova, necessary for the narrative so that Jim will later know how to save the ship from a collapsing portal thing, and a scene where the gravity on the ship gets turned off and on. Speaking of that gravity off and on scene, if the gravity is turned off, and they are in deep space, which apparently they are, based on the lack of gravity, although they are also floating above a giant space station large enough to have vegetation covering its surface (MOVING ON) and NOBODY IS IN A SPACE SUIT then HOW IS ANYONE BREATHING? And speaking of all of this, ok, yes, the sails LOOK awesome but exactly what are they doing and what space winds are they flying on, exactly?

Treasure Planet, of course, came after a long, long string of space opera films that happily ignored science (Star Wars and your sequels, we are primarily looking at you), and the steampunk town nestled in a crescent moon where everyone breathes freely is hardly the worst violation of physics in film history (I’d jump on you, Cloud City in Empire Strikes Back, but let’s face it, you were hardly the worst example either). It’s also part of a long series of animated films that often ignored the rules of basic physics (hi, Tarzan). Had Treasure Planet stayed in that mode, I expect things would have been fine, but unfortunately, despite mostly trying to ignore physics, the film also has at least four separate scenes using physics for plot. It creates a disjointed effect.

Also disjointed: many of the jokes in the film, including, for instance, a Star Trek joke, and a moment when B.E.N. sings “A Pirate’s Life For Me.” They’re meant to be the same sort of joking references to contemporary culture that had filled Aladdin and Hercules. But while this worked well for the self-aware and never particularly serious Hercules, and for the magical, not entirely part of his world in the first place Genie of Aladdin, here, it works less well. First, Treasure Planet is not a comedy, let alone a self-aware one. Second, the jokes are told by multiple characters, none of whom have any reason to refer to contemporary culture. If Treasure Planet had stuck to one or two of these jokes, it might have worked, but the awkward contemporary references against the deliberate 19th century design against outer space creates a feeling of, well, awkwardness.

But the biggest problem is that Treasure Planet takes a story that, for all its adventure and pirate fantasies, remains strongly grounded in realism, and transforms it into an outer space adventure with no realism at all. In Treasure Island, the characters have to deal with corpses, poorly made boats, the logistics of getting the treasure back to Britain without everyone stealing it, and limited stores of food, water and ammunition. Characters get sick, drunk, pass out, and die. That—and the high death count—adds not just a realistic touch, but a genuine note of suspense and tension.

Three characters do die in Treasure Planet—but we don’t get to know any of them, and none of them, even the upright, honorable Arrow, get a lot of mourning. This isn’t just in contrast to the book, but is also in stark contrast to other Disney animated films, which usually feature sadness and crying whenever anyone dies, even when that character returns to life just moments later. Oddly, those fake-out deaths end up having a larger emotional impact than the deaths here, largely because of the muted emotional reaction. Here, since almost nothing has an emotional impact, very little feels real.

The one exception is the relationship between Long John Silver and Jim. It’s a testament to Stevenson’s creation that Long John Silver transitions so fluidly into this film: he’s the hands down best and most intriguing part of it, as he was in the original book, and not just because of his great line about an eyeball. He’s also the centerpiece of the best relationship in the film, the father-son bond of sorts he develops with Jim, transformed in this film from an honorable, upright boy to a troubled boy still angry that his father abandoned him. Starting, as it does, with mutually suspicious dialogue before shifting into a wary trust, in some ways it works even better than it did in the original book, which did not really bother to waste time on developing any relationships, father/son or otherwise. Here, the relationship helps explain Long John Silver’s shifting alliances, as well as Jim’s decision not to abandon him in return. It helps that Long John’s advice to Jim is actually good advice—better than the advice Jim gets from his other quasi father figure, Doppler, or indeed from anyone else in the film. Not surprisingly, Long John becomes one of the few people Jim will listen to. Until he meets the robot, but that’s less “listening to” and more of “trying to make sense of so I can find this treasure and a way off the planet.”

Unfortunately, the other relationships in the film tend not to fare as well. For instance, the film starts out lightly teasing the possibility of some sort of future relationship between the dog-like Doppler, apparently an old friend of the family, and Jim’s mother, something that gets completely dropped when Jim and Doppler decide to go after the treasure. They leave Jim’s mother behind, and mostly out of the film. Doppler then meets Captain Amelia, who has to correct him on multiple items, something he resents. They then barely interact at all for several scenes, exchange one significant and completely unearned glance at the film’s climax, and show up in the final frames, married, with quadruplets. I suspect there’s more here—something about dog and cat people biology, possibly, some slight visual joke that isn’t translating that well to the screen—but the bottom line is that I ended up feeling that maybe, just maybe, I’d been a little harsh about some of the previous “what setup” romantic relationships in Disney films. At least Cinderella and Snow White assured us that their princes were charming sorts of people. Here, we’ve had some resentful dialogue, and then, quadruplets.

Speaking of those relationships, I do find one more thing about Treasure Planet odd—not bad, certainly, but odd. By the time they started work on Treasure Planet, Musker and Clements had gained a certain reputation for featuring heroines tinged with more than a bit of eroticism. The cabaret song sequence in The Great Mouse Detective had almost gotten that otherwise adorable and inoffensive film a PG rating. Jasmine and Meg are regularly listed among the most “sexy” Disney characters, with Ariel not that far behind. Both Ariel and Meg are required to seduce the heroes of their films, and Jasmine uses seduction to distract the villain in hers. Treasure Planet retreats from this. The film has exactly two women: Jim’s mother and Captain Amelia. Both remain fully and modestly clothed in every scene; neither woman tries to seduce anyone, and although, as I noted, both are somewhat involved in relationships, “tacked on at the last minute” seems somehow a bit too kind a description for Captain Amelia, and Jim’s relationship with his mother is considerably less important to him, and to the film, than the relationships he develops with Long John Silver and B.E.N. the robot.

And Treasure Planet is unusual in another way: it’s one of only two Disney animated films not to have a romance for a protagonist old enough to have one. Disney had, of course, produced a number of non-romantic films—Pinocchio, Dumbo, Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, The Sword in the Stone, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, The Great Mouse Detective, Oliver and Company and Lilo and Stitch – but all of these had featured younger protagonists.

The other exception, The Emperor’s New Groove, features a happily married couple and whatever Yzma and Kronk are—that’s not clear. Treasure Planet has no happy couples, until the unexpected significant look and the quadruplets at the end, and no real romance—quite possibly why those quadruplets were thrown into that final scene.

But they were not enough to save the film. Treasure Planet debuted to kind to lukewarm reviews, but even with the kind reviews, viewers apparently did not want to see pirates in space. Even pirates making the occasional Star Trek joke and singing “Yo Ho Ho Ho a Pirate’s Life For Me In Space.” Treasure Planet bombed at the box office when it was finally released in November 2002, earning only $38 million in the United States. International receipts only bumped that total up to $110 million. DVD and later streaming releases did little to improve these figures.

Officially, the film cost $140 million to make (actual costs are rumored to be considerably higher), with marketing costs bringing this up to $180 million (actual costs are again rumored to be considerably higher) making Treasure Planet not only the worst performing Disney animated film in years, but, as of this writing, the worst performing Disney animated film of all time, managing to lose more money, even adjusted for inflation, than previous box office flops The Black Cauldron and Sleeping Beauty—combined. As of this writing, it is still listed as one of the most expensive box office flops of all time. Worse, The Black Cauldron had at least managed to recoup costs in international releases, and Sleeping Beauty, of course, had eventually more than recouped its costs in later releases and as part of the Disney Princess franchise. Treasure Planet had little hope of doing either.

The financial news could not have arrived at a worse time for Disney, then mired in executive infighting that did not end until 2005. Or for Disney Animation, which by this time, with the sole exception of Lilo and Stitch, had suffered through a solid decade of slowly declining box office receipts and critical praise, and was now contending with not one, but two successful rival animation studios. That one of these rivals, Pixar, had developed its earlier animation programming while working with Disney, and that the other rival, Dreamworks had been in part founded by former chairman of Walt Disney Studios Jeffrey Katzenberg (see why I name dropped him earlier?) only made the situation more painful—especially since Katzenberg had been deeply skeptical of the Treasure Planet project to begin with.

By this point, Roy E. Disney, Michael Eisner, and other Disney executives did not agree on much. Indeed, they agreed on so little that Roy E. Disney was already starting the process that would lead to Eisner’s ousting. But, as the executives before them had right after Sleeping Beauty and The Black Cauldron, Disney, Eisner and other executives did agree that their animation department had a problem. They looked at the box office success of their rivals at Pixar and Dreamworks. They noticed a common factor. No, not well told stories, or popular characters, or even Buzz Lightyear.

Computer animation.

Dismissing the traditionally animated Lilo and Stitch as an outlier, Disney executives made a momentous decision:

Going forward, the studio would—with one exception, to be discussed in a few more posts—stop creating traditional, hand drawn animation, the very art form that Disney animators had focused on since the creation of Mickey Mouse, the art form they had transfigured into full length animated films, the art form that they were still selling (in the form of hand drawn, hand inked and painted cels) in their theme parks, the art form that had, for all intents and purposes, launched their company.

A history ended with a single pirate film.

Instead, the studio would follow the lead of the rivals it had helped create.

Which means it’s time to skip a couple more films:

Brother Bear is a Disney original. Notably, it’s one of the few films to change aspect ratios midway through the film, an effect somewhat lost on the Netflix transfer. Watch this on Blu-Ray. It was also the last film animated at Disney’s Florida animation studio. Traditionally animated, it did decently enough with critics, the box office and later merchandise sales (you can still find related clothing and pins), but ended up being completely overshadowed by a little film called Finding Nemo.

Home on the Range is another Disney original. It’s not exactly one of the better Disney animated films, but if you ever woken up at 3 am thinking, wow, I really want to hear Dame Judi Dench voicing a cow, then this is your film. Traditionally animated, Home on the Range struggled through development, going through multiple pitches and storyboard treatments before switching directors mid-animation. It performed poorly at the box office, failing to earn back its production costs, and ended up getting completely pounded by a little film called The Incredibles.

Next up: Chicken Little, a film that appeared in 2005—one of the few years of that decade without a Pixar film.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

This movie has always made me sad. It could have been so good, it just failed for for all the reasons expounded upon above.

This was one of the Disney movies that came out by the time I was too old to really care about seeing Disney movies (although since then I’ve been trying to hunt down and collect the ones I don’t see), so I ordered it in time to watch it for this rewtach.

I really, really liked it. I can definitely see why maybe it wasn’t a big hit (not a musical, not a romance, etc) but I still really liked it – it was definitely something new and different, it was gorgeous, I liked the coming of age/father figure type themes, I did kind of enjoy the rock-y soundtrack, and I just generally enjoyed it. Probably not in my top 10, but still above the halfway point.

As for some of your questions regarding the spaceport: who cares? That’s basically my thought on that. I think it’s definitely a Rule of Cool kind of thing. I don’t really care how it holds its shape, haha. And actually I thought the spaceport moon was kind of ‘within’ the atmosphere of the planet but I could be totally wrong on that.

Also, my understanding is that the ships are flying on the aether, which is kind of an old notion of what was in space. So I kind of dug that.

I think you are probably right about the general character development/emotional payoff in the movie (and the general inconsistency of the way the science is applied), but I guess I don’t care.

Rearding Doppler/Amelia – interestingly, I didn’t see a setup for Doppler and Mrs. Hawkins at all; I guess I took at face value that, no, they really are just friends. And I didn’t find the Doppler/Amelia relationship really surprising at all because I got the impression that mutual respect was slowly being built (especially off screen). I also really enjoyed Amelia as a character and some ways kind of enjoyed their relationship more for it being just something that is happening between two adults and not the main focus of the film. As much as I really dig the Disney romances, I can also appreciate that this movie didn’t go that route for Jim.

Anyway, it makes me sad that it flopped SO horribly because – again, while I can agree it’s not the greatest film ever, it’s definitely not the most horrible either. I don’t really care for a lot of Dreamworks films and honestly, think this was more entertaining (and aged better) than most of them. It also makes me sad that this is what drove them to stop traditional animation, as I really love that, and it seems like such an obvious ‘marketing’ type of decision, instead of focusing on actual story/characters.

I didn’t realize Brother Bear was an original…(I guess I assumed it was based on some folklore or something). But I haven’t seen Brother Bear, Home on the Range (I’ve actually seen about half of this on TV – I’ve heard it’s basically in the running for the worst Disney movie ever made, but the half I saw was just weird/bizarre enough to pique my interest so at some point I do intend to finish it.

Oh, man, Chicken Little. I completely forgot this even existed. There are a bunch of Disney movies from this era I was never even aware of until I started doing research into what the full canon was. Actuallly, I’ve heard this one is also pretty bad, so I guess we’ll have to see what I think when I see it. :)

I’ve tried to watch this as well as Titan A.E. a few times and just can’t do it, which is a shame because on paper they’re both right up my alley.

I will say, though, like a lot of bad movies the score for Treasure Planet is terrific. Ignore the generic songs and just listen to the orchestral tracks. I discovered it via Pandora, and it’s really good.

http://youtu.be/WC3PidaLO08?list=PL1492D1D5136CE5B2

I thought the sails were solar sails, being propelled by light photons. The ship had gravity generators, I imagine the space port would as well, and I also thought the spaceport is just that, not a moon but a manufactured city orbiting a planet. As for the air on the ship, the artificial gravity might be creating enough pressure to keep air in, and when turned off the air should’ve expanded away rapidly, unless the ship has some fantastical way to pressurize the space around the ship separate from the gravity. These are just quick thoughts so if I messed something up, my bad.

If there is one Disney Movie of the past 25 years that deserves a remake or re-imagining because the original is indeed broke, it’s Treasure Planet. Proof of concept nowadays for Disney is Big Hero 6 which is the closest in terms of tone and ambition, though it was based on a Marvel Property.

I always thought Treasure Planet would have done better as a Musical. Rock Opera or something. Would have been cool.

By far its biggest problem besides the ones mentioned was the one it shared with Titan A.E.: It didn’t know what its target audience was and neither did the marketers. I remember the reactions at the time being, “Is this supposed to be for kids?” “Is this for teens?” It could have been a unique kid’s movie or it could have been ambitious as a Teenager’s movie, but it tried to be both and it flopped.

I saw that one in cinema when I was eleven and I remember to have liked the movie. But than, again, I was eleven and of course all the things a grown and educated viewer will notice about it (Star Trek references, misplaced jokes etc.) went either unnoticed or was a source of mirth.

Haven’t seen it for… yes, almost fifteen years (and now I feel old…) and should maybe do a rewatch after reading your post. Just to see how I’ll like it :).

Seems a bit unfair to ask hard science questions of this movie, because I don’t think it was intended to be science fiction. Rather it’s space flavored fantasy like Star Wars and Flash Gordon. How does hyperdrive work? Why it works just fine, thank you! It’s all pixie dust, Tinker Bell.

Treasure Planet is one of my favorite movies ever (and I saw it as an adult). What makes it solid is complicated characters and rich innovative storytelling. What might have hurt this movie is its lack of appeal to mothers and girls.

I’ve seen this movie a couple of times, recently in Netflix, and it should be right up my alley, as the new Jim Butcher Cinder Spire series is, but this movie creates a giant feel of “MEH” in me. I don’t care for it. I find it entirely soulless. And I think party of this is what you mentioned about the lack of reaction in the characters themselves.

however, it does look beautiful is just that it doesn’t compensate for the characters being so bland except for Long John and Jim being an unbearable brat.

I have such mixed feelings about this movie! I adore several of the characters, while others are two-dimensional cardboard and/or downright irritating. (That damn robot is the latter; all the villains who are not Silver are the former.) And it was such a gorgeous set of setpieces, centered around a cliche central character (who admittedly got a great character dynamic with Silver) and then we had to have his idiot scholar friend tagging along, ugh, like we really need two comedy sidekick characters? Plus the cute comedy animal character? All three of those?

…and yet I still want to be Captain Amelia when I grow up.

Honestly, when I rewatch it on Netflix, I just fast forward through anything that isn’t a gorgeous setpiece, Captain Amelia, or the Silver/what’s-his-name musical character bonding montage. Such great pieces, to be mired in such a lurching movie!

This here…. Is my favorite Disney movie. Period. Something about it tickles all of my nerdy bones perfectly. I’ve always been enamored of the soundtrack.The songs during the Silver/Jim bonding montage and the first song for the end credits both were songs that I loved from the moment I first heard them. The story, for all its flaws, is just… wonderful. I love it warts and all. It and Titan A.E. hilariously enough. Both are among my favorite animated movies to ever come out.

I can’t help but feel you’re missing the movie in which Disney went back to hand drawn animation:

2009’s The Princess and the Frog.

I’m with Joe and Lisamarie — I really liked this movie and none of your criticisms — which may well be justified — bothered me. I only saw it once and I don’t remember the details, much, but it was beautiful to look at and not overly respectful of the book, which I always thought was much less wonderful than everybody seems to think. In fact, having read this, I’m sort of inclined to find it and see it again. Guess I must be one of those cult members.

@12. TsunamiJane: I’m reasonably certain that is the “one exception, to be discussed in a few more posts”. :-)

Having never actually seen Treasure Planet, I might go back and give it another go. I did really like Titan A.E. despite the flaws – it at least tried to reach for something great. This sounds like a bit of a beautiful mess.

Oh, and Chicken Little … good god, I’d blocked that from my memory pretty thoroughly.

Titan A.E.

As a child, I constantly confused them. One just cannot help but pile these 2 movies together forever.

It’s a strange movie: the SF was so trite and so redolent of the US in the 80’s (flying skateboard…) that I spent much of the movie regretting it wasn’t a straighter adaptation of Stevenson’s book. It was a superb movie, and such splendour would have beautifully served a faithful “Treasure Island”.

But Disney wasn’t into faithful adaptations. Still isn’t, really.

It is a shame what happened to this movie. It is no worse than many other sf movies or animated movies in the liberties it took, and it isn’t overly bad. It just came out at the wrong time. If they had said yes to pirates in space a couple of years earlier it would probably have been a hit. Just, by the time it came out it was not in the public zeitgeist. Sadly when it comes to box office success, the wrong film at the right time will beat the right film at the wrong time everytime.

Prior to the Read-Watch, I didn’t know this one existed. I hear “pirates in space” or “steampunk” or “space opera,” and can think only of the gloriously ridiculous Larklight books.

Didn’t see Titan A.E. either, except possibly the very beginning. Does it start with people seaching for a planet that still has “drinkable water and breathable air”? Because that concept terriefied me as a kid or possibly teenager and still does. I do not like post-apocalyptic stories, Sam-I-Am.

I remember at the time I thought “that looks like Atlantis: The Lost Empire again”, similar mixed-adventure tone and whatever. I’ve never been able to watch either all the way through so I can’t really compare, but it seemed to be in that already-established-as-bad vein.

I loved this movie. Just like I love the Japanese trains in space movies and TV shows (Night on the Galactic Railroad! Galaxy Express 999! OMG THERE ARE NO TRAIN TRACKS IN SPACE HOW CAN THESE BE WORTH WATCHING?!). This isn’t science fiction where ships sailing in space need to be explained. For crying out loud, ships are sailing in space! Isn’t it obvious that this is a fantasy where you either accept that or stay home and watch Black Sails (which I love too, but its gritty realism is a direct opposite approach to Treasure Island story-telling). Sometimes in order to enjoy stories, you need to accept that things like The Force just aren’t real and not applied in consistently scientific ways.

This movie is incredibly fun, but it’s obvious that it didn’t know who the audience was supposed to be. I saw it when I was an adult, and thought it was a terrible movie for kids. No wonder it flopped- a cartoon from Disney not really aimed at kids? The US wasn’t ready for that. Probably still isn’t, considering the way Miyazaki fares in theaters.

Blimey, until now I had no idea that this film existed.

I guess I’m in the minority that actually loved this movie. I really enjoyed seeing something new from Disney, and I LOVE space pirates! It was a beautiful film, and I enjoyed watching the relationship build between Jim and Silver. I’m not saying it didn’t have flaws, but overall I thought it was a great film.

I’ve only ever seen Treasure Planet once and not in theaters, but honestly. . .even if all the criticisms turn out to be true, and they might, those stills make me want to rush to Netflix RIGHT NOW, storytelling warts and science fantasy handwaving or no. I suppose I’m not quite in the Pixar camp where it’s 100% about story. . .visual beauty counts too, for me.

I can’t get over that picture of Amelia, Doppler, and the babies. It’s the cutest thing I’ve seen online since you posted that picture of the snuggling mice in The Rescuers.

Count me in the vocal minority who likes this movie. I didn’t see it in theatres as a teen, so I guess that says something for the criticisms being very legitimate (up until then my family had solidly attended most Disney screenings), but when I saw it later on video I really enjoyed it. I didn’t think too hard about the science because I took the world for what it was: invented and not ours, with its own set of rules. The visuals and imagery are great, the music is great (love when it pops up on my Pandora scores station), and the characters/story has the same rousing adventure feel that the book inspired generations before.

@2: I completely agree regarding Doppler/Amelia, and was also surprised at the reference between a “thing” between Mrs. Hawkins and him. I got the vibe that they both felt paternal toward Jim; maybe he might be angling for a bit more, but certainly not she. And sure, Dopper and Amelia are an oddball couple, but I’m a sucker for those, and I saw a real evolution in their relationship throughout the film so I felt it completely justified (as much as any relationship carried out over the course of a movie’s short timelength can be).

Also, 100% agree with “more for it being just something that is happening between two adults and not the main focus of the film.” It’s nice to see romance handled as just a natural part/slice of life, alongside other adventures, without it being the main story/end game. I liked the fact that this story was a change of pace from other Disney movies at the time.

OK, I also have to admit that I enjoy steampunk, and just really love the whole concept of this film. That probably makes me biased.

But I agree with other posters that this movie really came out at the wrong time to find its audience, and was poorly marketed to boot. I can see families today saying “Pirates in space? Cool, let’s go!” Not so much then.

@26: does make you wonder if it was released, would it become a Stempunk cult film?

One thing I think hasn’t been mentioned here is that back in 1993, Tor Books actually published a Treasure Island IN SPACE! novel, namely Charles Sheffield’s Godspeed. It isn’t all that good or memorable in my estimation (I read it not long after a reread of Stevenson’s novel, which didn’t help): I was reminded of it because Phoenix Pick chose it as this month’s free ebook.

I was on a Disney Cruise last week, and there WAS some art from this visible, I think–but I only recognized it because this blog series let me know the movie existed. (On Pirates night we were in the Animator’s Palate dining room.)

I’ve actually never watched this movie, but surfing around YouTube and I found this lovely gem of the song “I’m still here.”

It made me really want to watch the film. Maybe they will give it another shot?

I think it was specifically mentioned by someone who worked on the movie that space was replaced with aether, so that they could have sailing ships and more elaborate backgrounds. I thought this one was all right, but I don’t remember a whole lot of it.

“Home on the Range,” to my mind, is underrated. The thing is, I knew practically nothing about it before seeing it, other than that it was intended as the last Disney film with hand-drawn animation. It’s amusingly bizarre.

I’m now three or four chapters into Alastair Reynolds’ book Revenger and I’m starting to think that this book is what Treasure Planet should have been adapted from.

the movie takes place in an alternate universe. The Space in this universe is called Etherium, it’s said at the beginning of the movie, and allows creatures to breath in (thus why you can find Orcus Galacticus in it) and winds you can sails with.

Released in November 2002? So close… If only they’d waited for a little film called Pirates of the Caribbean to come out… pretty sure Treasure Planet would have been buoyed up by Curse of the Black Pearl and its revival of all things pirate-y. It’s a shame because there are many good things about this film. I saw it first as an adult and was actually really impressed by the mature tone and the development of the relationship between Jim and Silver. I also really liked Captain Amelia but I love Emma Thompson so that probably influenced me.

I know that it has been a while since the publication of this article, but I want to make a few points.

First off, Cresentia is not an actual moon. It is an space station that is built to look like a moon. Also, it orbits their home planet. Since Cresentia is man made, it would make sense that it would be using artificial gravity generators like they do on the ships.

Second, the reason why people can breathe in space both in Cresentia and in space is because they are in a specific layer of space called the Etherium, which is said in the opening narration of the film. Hell, it also says the “winds” of the Etherium, meaning there are winds, henceforth the sails on the ships. They even call the ship sails “solar sails,” meaning they use solar energy, kind of like solar panels, to move the ship. And considering the “winds” mentioned at the beginning, that means the solar sails are using solar winds, which do actually exist in our universe as well. Also, that brings me to my next point-

Why is it so bad that the movie is borrowing some science from our universe to serve its own? Like, why can’t it have a big supernova in the story? Why can’t it just be a part of the film’s universe? Stars do exist in their universe, right? Stars exist in our universe. And stars in our universe turn into supernovas, so why can’t the stars in their universe do the same? The fact that there is a supernova in the movie is borrowed from our reality, but it’s not to have the film appear scientifically accurate. Supernovas just happen to exist in their universe. That’s it.

The physics of this universe are its own physics, which include people breathing in space, ships traveling on solar wind, ships having artificial gravity, and suns turning into supernovas. Hell, I highly doubt the supernova in the film is scientifically accurate to one in real life. But that doesn’t matter, because that is how it happens in their universe. I emphasize, “their universe,” not ours. Scientific accuracy is not at the forefront here, and it never was, because the film is fantasy, not science fiction. A more accurate term would be science fantasy, akin to Flash Gordon and Star Wars, but still a type of fantasy. Science fiction and science fantasy are not synonymous. Science fiction is still grounded in the realm of science, uses scientific logic to create fictional stories. Science fantasy does use elements found in science, but not in the same way as science fiction. Science fantasy takes them and uses them simply as elements for a primarily fantasy setting. When George Lucas was coming up with Star Wars, I highly doubt he thought of the logistics of light sabers. Also, in The Clone Wars series, they have explosions in space (which happens in almost every Star Wars incarnation), yet people still die in the vacuum of space like how a real person would. So, what makes that okay and not what Treasure Planet does? The point is that when the film has scientific aspects that mirror the ones in our world, that isn’t because it’s trying to look scientifically accurate. They are just elements in their world, and it just so happens that they are a part of our world as well. Creators use aspects of our own world to help create theirs all the time. You seem to be trying to view a science fantasy story through a science fiction lens.

Also, you say that what made Treasure Island good was its sense of realism, and adapting that story into a fantastical adventure in space with little realism didn’t work, yet you don’t go into why. You do go into why it works in Treasure Island, and that’s fine, but your don’t explain why Treasure Planet’s more fantastical approach doesn’t work for that kind of story. Since Treasure Planet is not trying to be realistic here, it has to be great in its own fantastical way. But still, you don’t explain why that approach doesn’t work. Is it because they don’t encounter dead bodies or something? If it was trying to be realistic in the way the original novel is, then okay, but its obviously not and its trying to do its own thing. Disney has always taken other stories and made them into their own things, so I don’t understand why that’s a problem here.

I do sort of agree with you on the relationship between Dilbert and Amelia. For one, their relationship didn’t come out of nowhere. The film does show Dilbert and Amelia talking to each other and growing to like one another. Hell, Amelia tells Dilbert he has gorgeous eyes. However, I do agree that their relationship felt forced and obligatory, and I would have been fine if those just formed a mutual respect for one another. But that doesn’t bother me very much here.

I also agree with you on the humor and how out of place a lot of it felt. Once again, I don’t mind it, even B.E.N., but I do understand the frustration.

Other than those two things, I do not agree with you assessment. You leave out certain information that would actually answer your questions, and treat this movie like a science fiction story when it’s science fantasy, which once again, are not synonymous.

This was kind of ranty and rambly, but I just wanted to at least voice my disagreements in your article.

Regardless of your review I liked this movie when it came out and still like it. It is a good story, fun to watch . Some of us really don’t care about how the science works in a fantasy movie. It’s a story for goodness sake.

Very good analysis. For me it’s a mystery why this movie eventually achieved such a cult status. And fans of the movie get really very defensive and don’t respond well to criticism Personally I’m not even such a great fan of the much praised art work although it’s technically brilliant. Maybe, too brilliant, if that even makes sense. And in this movie very little makes any sense…

Personally I’m not even such a great fan of the much praised art work although it’s technically brilliant. Maybe, too brilliant, if that even makes sense. And in this movie very little makes any sense…

But IMO the main reason why the movie is a failure, is this: it is based on an iconic novel for young adults which is absolutely perfect! Treasure Planet simply cannot compete with Stevenson’s Treasure Island! Everything in the novel is done better than in the Disney space version. Of course this is unfortunately true for almost all silver screen versions of the novel – although there is one four-part version from the 1960s for European tv, which comes very close. Mainly, because it sticks very closely to the original plot, which is adapted in a very realistic fashion, and because it has with the English actor Trevor Dean a brilliant Long John Silver. Also – like in the book – Jim is not a kid but a teenager, which adds more gravity and realism (and this is actually one of the few things which “Treasure Planet” gets right). But as much as I enjoy this particular TV version, it’s too dated for contemporary viewers, and the special effects and production values are not adequate any more.

Stevenson managed to write the ultimate romantic pirate adventure novel. And while two two thirds of the novel are set in an exotic scenery, it’s the realism and the relatable character which makes it work so well. Treasure Planet gave up this realism for no discerneable reasons – except that 18th century-style pirates in space must’ve sounded kinda cool at the time

I feel really bad for Clement and Musker, though :( Treasure Planet was their dream project for so many years, and they really tried to do something different and ambitious. How did they cope with the failure of their dream project?

The thing is, why did they add the SF theme into the movie? It’s so Earth-nautical that it makes no sense whatsoever for it to be set in space at all! If they wanted ships and rigging and peg legs they could have used the original setting. And if they wanted to make it SF they could have made it modern and shiny. This weird steampunk-esque hybrid just doesn’t work for me.

@vinsentient, I totally agree! This weird mixture of oldfashioned 18th century look, steampunk and sci-fi doesn’t make any sense whatsoever, and therefore it doesn’t work. One is constantly taken out of the movie and distracted for no good reason whatsoever. I also don’t like the mixture of animal-human hybrid characters and characters who are totally human. They should have made them all animals and animal-hybrids or all 100% human and should not have created two classes of characters, which also leads to needless distractions and uncanny-valley sensations.

I think that a Treasure Planet plot with pirates in space could’ve worked just fine if they had built a complete and coherent sci-fi setting a la “Star Wars”. In the beginning of Star Wars Han Solo was some kind of space bandit after all who dealt with all sorts of intergalactic crooks. Rogue pirate space ships in a future setting are certainly a viable concept. John Silver as Cyborg with the cute morph as sidekick and Ben Gunn as a slightly unhinged robot could also have worked well in a different setting – just like Marvin, the moody robot from “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”. But this world would’ve needed to be developed in a plausible and coherent fashion.

Another problem of Treasure Planet is that the humor doesn’t work very well – but neither does the drama. And the ideas of the creative team were apparently never really controlled and underwent no plausibility checks whatsoever – and therefore they just went overboard and created one of the weirdest Disney movies ever.

I liked this analysis, and I actually read all the comments, I see that the movie has apparently many fans these days – or the fans are more vocal than those who don’t care for the movie. I belong to the latter group. Since others have already listed many reasons why the movie doesn’t work for them, I will only mention one issue: the weird setting in an alternate universe which is a mixture of 18th century nautical setting with sci-fi elements. It has been pointed out that an alternate fantasy universe can have it’s own laws of physics, and it’s unfair to ask for realism. The world of Star Wars is not realistic either after all. Point taken. But the problem with Treasure Planet is that it used well established 18th century nautical and pirate iconography which is well known (in large parts thanks to Robert Louis Stevenson’s wonderful novel Treasure Island) to the audience. But this iconography is then married with sci-fi and phantasy elements. The problem with this is, that the audience doesn’t really get into the phantastic elements because large parts of the iconography suggest a different setting. That’s the reason why so many scratch their heads and say”…this doesn’t make any sense!” This would not have happened in a more straightforward sci-fi setting. I don’t think that the movie would’ve done much better if it had come out at a different time because the fundamental problems would’ve been the same. Also, as others have pointed out, the plot and the humor are kind of weak. If the story had been more captivating or if the movie had been a lot funnnier with more memorable characters, the weird setting would not have been so noticeable and we would’ve said “OK, it doesn’t really make sense – but it’s a great story!” Treasure Planet does not deliver that. And in the end a movie cannot thrive on beautiful optics alone.

My four years old son just loves this movie. Rock-y songs, space pirates, surf in spaaaaace…

I find it gorgeous and entertaining, and most of all I consider it a great adaptation of the D&D setting Spelljammer… I find it unusual that nobody pointed that out.

doppler and jim’s mom sarah are intended to be long time friends with more like a brother-sister than anything romantic. definitely dont get where you got that from lol, but this movie rules imo!